git Workflows – how to organize branching¶

Summary:

- Centralized

- Feature branch

- Gitflow

- Forking

Most of this section comes from the Atlassian workflow overview, including the figures (under the CC-au license). I like this presentation of git workflows, because it starts from the SVN-like model that many are comfortable with, and adds one new concept for each successive workflow. This way, one can partition their understanding and choose the level at which they wish to work.

I’m only going to summarize the workflows here to serve as a reminder about their major points. If you are unfamiliar with them, go read the overview - it doesn’t take too long.

1) Centralized (SVN-like)¶

The centralized workflow is using git like SVN, which means using the git “master” branch the same as SVN “trunk” and not really branching besides that – all changes from everybody get committed to master.

Note also that in this model, rebase is probably more useful than merge, since

rebase preserves a more linear history

which looks more SVN-like. So use things like git pull --rebase.

2) Feature branch (centralized + branching)¶

This model uses branches other than master for all development work; a new branch is started for each feature or topic e.g. “cg_diagonalization” or “issue-#1024.” Since no development work is done in master anymore, it can be curated to represent the official project history. Feature branches get pushed to the central repository, where a pull request is created when the feature is ready to become part of the official code base or when the developer wishes to otherwise initiate discussion about the code.

Some advantages of feature branching over the centralized workflow:

- the master branch will never contain broken code

- multiple developers can work on a single feature without disturbing the main code base, or other concurrent feature development

- using pull requests now makes sense (PRs make code review, automated integration testing, and many other positive things more convenient)

3) Gitflow (Feature branch + organization and conventions)¶

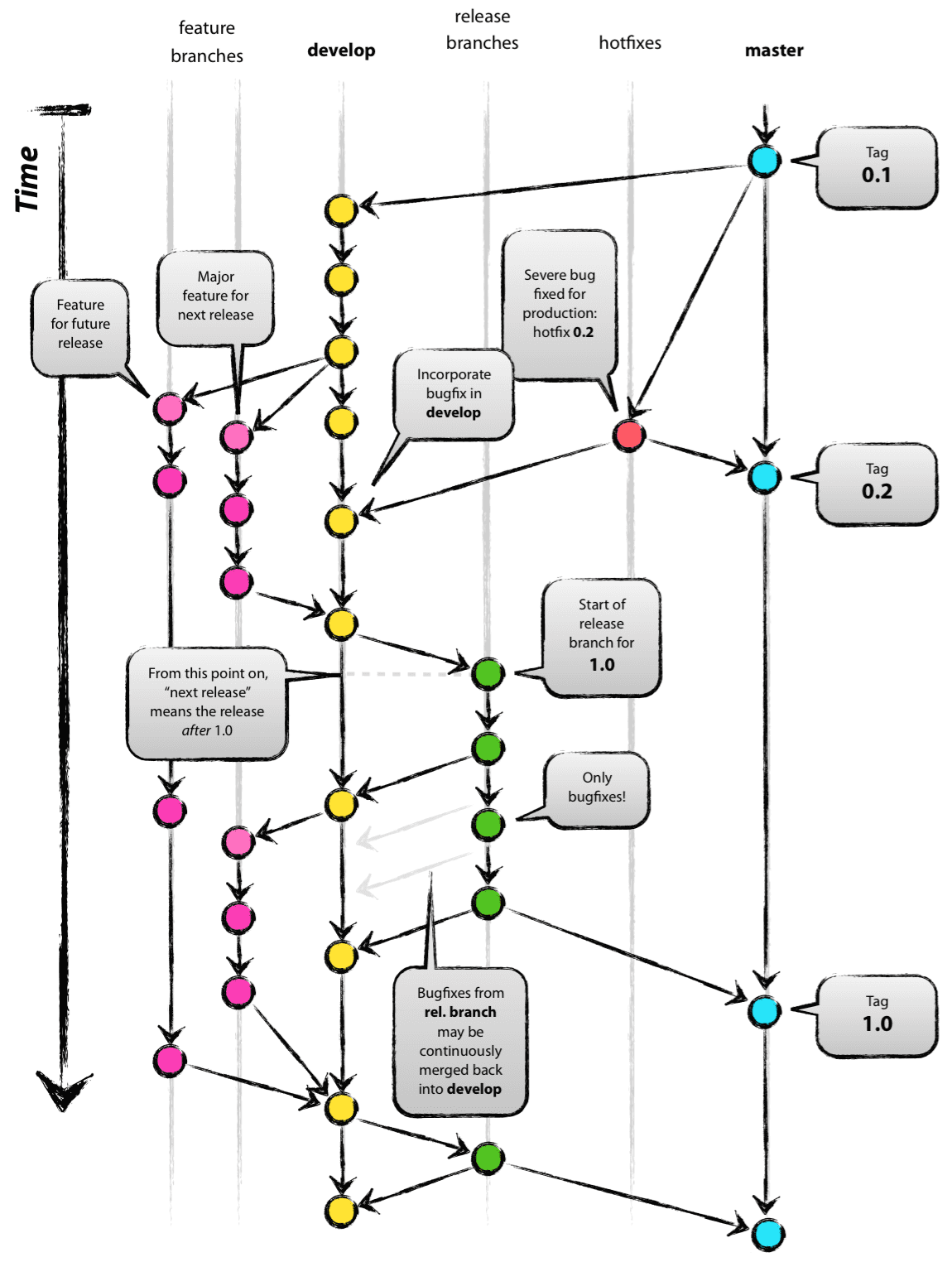

In the Gitflow workflow as introduced and covered in detail by Vincent Driessen, feature branching is used with some added ground rules for how branches are named, where they originate from, and where they get merged/rebased to. The original post, [“A successful Git branching model,”](http://nvie.com/posts/a-successful-git-branching-model/) is well worth a read.

At the backbone of the project are the master and the develop branches. Supporting branches are all features, releases, and hotfixes. The figure and table below summarize how all of these branches work together.

(Author: Vincent Driessen. Original post: nvie.com/posts/a-successful-git-branching-model/ License: Creative Commons BY-SA)

| naming convention | May branch off from | Must merge back into | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

master |

(none) | (none) |

|

develop |

release |

release |

|

| (anything) | develop |

develop |

|

release-* |

develop |

develop, master |

|

hotfix-* |

release |

master, develop |

|

To experiment with this workflow and practice merging, rebasing, branching, etc., the gitflow_history.sh will generate a repository with the exact history shown in the figure above.

4) Forking (any workflow + forking for collaboration)¶

Forking isn’t a new iteration on the previous workflows; it can be applied to any branching workflow. It is more for defining how developers interact with the project repository. Here, nobody clones the main project repository, but rather forks their own copy. This means that everybody pushes to their own copy, and pull requests originate from forks outside of the project repository, rather than from branches that live on the main project repository itself.

Doing this allows at least a couple of advantages/conveniences:

- allows safe integration of new code, even from untrusted contributors (since they don’t need access to the project repository)

- even the project maintainers don’t need a working (non-bare) copy of the project repository